not well known and often misunderstood. Let's see if we can

fix that.

Proto-parliaments: The Witenagemots

contained a handful of Witenagemots (meetings of wise men)

acted as advisory bodies for the king. The Witenagemots were

assemblies comprised of powerful landowners. Beyond these

two facts little is known about them. We don't know if the

Witenagemots were an aristocratic evolution of the earlier Germanic folkmoots (general assembly) nor whether the

Witenagemots had any formal powers beyond that wielded by

individual members. We do know that there was no single

'national' Witenagemot and that the summoning of the

meeting was a prerogative of the king. Further, the

Witenagemots had no set meeting location but would meet at

least once per year.

However, in the tradition of the Witenagemots we see a first

principle of the English Monarchy taking shape: that the king

rules in consultation with others.

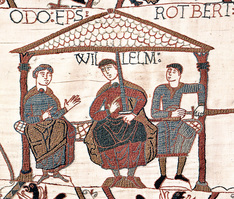

The Normans: Birth of the Curia Regis

William and his brothers

William and his brothers was crowned King of England.

The various Witenagemots

ceased to be (partially due to so

many of the Anglo-Saxon elites

being dispossessed of their

lands. The Normans had their

own tradition of aristocratic

advice in the form of the Curia

Ducis (duke's council). Across

Europe the situation was much the same with kings and great

lords having bodies of advisers to assist in governing.

Once William the Conqueror was secure on the English

throne he created the Curia Regis (King's Council). Like the

Witenagemots it was comprised of the leading nobles of the

day. It differed in most other respects though. The Curia Regis

had two forms; the Magnum Concilium which was summoned

by the king to discuss issues of national importance and the

Lesser Curia Regis which was in session continually and

traveled with the king. The two types of Curia Regis were

considered to be the same body and not separate entities.

Indeed, the membership overlapped a great deal.

In this body we see the beginnings of two important

developments: a cabinet-like group and the creation of a

single national deliberative body.

The Loss of France: Renewed Focus

King John of England (in his role as Duke of Normandy).

King John attempted to get them back but required a great

deal of money to do so. While many of England's barons had

also had lands in France the loss of those lands effected them

differently. The Norman nobility's French lands had served as

a distraction from the affairs and concerns of England. When

those lands were lost they began to focus more on English

affairs. King John's war began to look to them as a foreign

adventure. Failure in 1214 compounded this view.

The Angevin kings had been able to use this distracted

nobility to rule via 'force and will'. That the nobility made a

great deal of money from their continental possessions kept

everyone content, if not happy, with the situation. The loss of

those lands made King John's heavy taxation and refusal to

consult his barons into a major grievance. The belief that the

king should rule in accordance with custom and the law was

greatly strengthened.

While the loss of lands in France had no immediate effect on

the evolution of Parliament, it was necessary for the future of

the legislative branch. A nobility content to be ignored by the

king as long as their estates were prosperous would never be a

firm foundation for a body such as Parliament.

Magna Carta: Misunderstood Document

by his nobility. That the king and his nobles were not on

friendly terms is best symbolized by the meeting location; a

bit of watery land beside the River Thames unable of

supporting cavalry. The charter reaffirmed the old rights of

the nobility and certain legal protections.

The Magna Carta has taken on an importance over the years it

likely never had when it was first signed. It has come to be

seen as the first stirring of constitutional government. In this

short history of Parliament it is important because it failed.

Neither side lived up to their obligations and war returned.

King John then had the misfortune to die and leave a young

heir.

Henry III: King John Redux

of barons his own rule mirrored his father's. Lack of

consultation gradually led the barons to lose faith in him. The

Magnum Concilium was at this point only called for the

approval of new taxes. It was certainly not called on to advise

the king. The barons eventually decided that they had had

enough and refused the king's latest tax request. In 1258 King

Henry III faced a major financial crisis and agreed to a set of

limitations known as the Provisions of Oxford. A Parliament

would meet three times per year to oversee the performance

of the bureaucracy. However, the barons proved unable to

work together and the king returned to ruling arbitrarily.

A new round of rebellions broke out led by Simon de

Montfort, Earl of Leicester. The king was captured in 1264

and for the next fifteen months Simon de Montfort ruled in

the king's name until his defeat by the soon-to-be Edward I.

The reign of Henry III confirmed the old ways were no longer

working. The king wanted to govern effectively, the barons

wanted to be consulted. Neither the king alone nor the barons

alone had been able to effectively govern the country. It fell to

the new King Edward I to find a way to reconcile royal

authority with baronial power. He would do this through

Parliament.

King Edward I: Increased Royal Power Through Parliament

summoned a Magnum Concilium that for the first time

included the shire knights and burgesses as well as the

nobility. This move was meant to strengthen his hold on

power by widening the interested parties beyond the nobility.

King Edward I would likewise call both groups to Parliament

often during his reign. The king experimented endlessly with

Parliament's composition and its power and role remained

fluid.

Perhaps more importantly, King Edward I began to use

Parliament to make statutory law on a scale never before

dreamed of. I have consistently used the term 'deliberative'

rather than 'legislative' to describe the various councils and

assemblies detailed in this article. This is because in England

laws were considered a matter of custom, not statute. The

king was responsible for interpreting and clarifying custom

but could not change it. Of course, it is a thin line between

interpreting law and making it. Some kings had been

lawgivers in practice but never much in theory.

This is contrary to a certain narrative that claims the ability to

legislate was wrestled away from increasingly arbitrary kings

by Parliament. This is not the case. The monarchy gained the

ability to legislate through the creation of Parliament.

By using meetings of leading barons, churchmen, knights, and

townspeople King Edward I was able to pass legislation

without the worry it might cause a revolt. Throughout his

reign Parliament was very much his creature and he used it to

strengthen the monarchy's authority.

Parliament had been born.

I hope you have enjoyed this brief look at Parliament's beginnings.

Loyally Yours,

A Kisaragi Colour

RSS Feed

RSS Feed