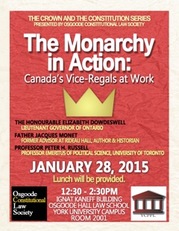

the Osgoode Constitutional Law

Society (OCLS) and the York Centre for

Public Policy & Law (YCPPL) held a

series of talks at Osgoode Hall Law

School on the topic of the Crown & the

Constitution. On January 28, 2015, we

held the second event in our speakers’

series, titled “Monarchy in Action:

Canada’s Vice-Regals at Work.” As part

of this event, Her Honour Elizabeth

Dowdeswell, the newly installed Lieutenant Governor of

Ontario, was joined by two eminent Canadian academics, and

experts in the field of Canada’s constitutional monarchy--

Father Jacques Monet, and Professor Peter Russell.

The following is a brief synopsis of each speaker’s

presentation. For those who are interested in the full hour and

a half presentation, I have included a link to the mp3 of the

event below.

Lieutenant Governor of Ontario

Her Honour began by discussing her role as the Queen’s

Representative in Ontario— an office which she described as

the product of a slow evolution from British colonial roots, to

its modern incarnation as the representative of the Crown in

Right of Ontario. The office represents our achievement of

responsible government, which Ontarians have enjoyed since

the 1840s. The Lieutenant Governor, representing the Queen

of Canada, is the protector of democracy and parliamentary

conventions in the province, and is hugely important to

understanding the historic and enduring relationship between

the Crown and Canada’s Aboriginal peoples.

The Lieutenant Governor has two principal constitutional

roles: (1) the legislative, representing the Crown in

Parliament; and (2) the executive, i.e. the Crown in Council.

Reading the Speech from the Throne, providing Royal Assent,

and granting requests for prorogation or dissolution of the

Legislature are all examples of the legislative role, while the

executive side includes the approval of Orders in Council for

the day-to-day governance of the province, as well as ensuring

that there is always a premier and cabinet to run the province.

In other words, the executive role is something akin to the

Chief Executive Officer of the province. Citing Walter

Bagehot, Her Honour continued by referencing the famous

three constitutional rights of the Sovereign and her vice-regal

officers: (1) the right to be consulted; (2) the right to

encourage; and (3) the right to warn—all three of which were

apparently exercised in some form or other by Adrienne

Clarkson during her term as Governor General.

Further, the Crown also has an important role in supporting

community service, and representing the citizenry. Canada’s

vice-regal officers spend the vast majority of their time

undertaking public engagements and representing the Queen

of Canada in celebration of that which unites us as citizens.

This part of job plays a key role in enhancing social cohesion

and promoting a wider Canadian identity, free of the

partisanship of politics. The Vice-Regal Suites at Queen’s Park

presents a neutral space for community groups, and people

from all walks of life to enjoy. It is also at Queen’s Park that

Her Honour welcomes diplomatic leaders from around the

world on behalf of all Ontarians.

Her Honour also recognizes provincial excellence through

Ontario’s provincial Honours system, conferring such things

as the Order of Ontario, or medals for good citizenship,

voluntary service, or bravery. The Lieutenant Governor

travels widely throughout Ontario in her public role, with the

overarching theme of her mandate being the promotion of

Ontario’s role in a global world. Her Honour is an advocate

for a clearer transparency and understanding of the role of the

Lieutenant Governor, which is essential if the Crown is to

retain its relevance in the 21st Century. In this spirit, Her

Honour uses every public event as a sounding board to learn

about the various issues that are important to Ontarians.

Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the University of

Toronto, Peter Russell is one of Canada’s leading

parliamentary scholars. Recently his focus has been on

minority governments and constitutional conventions related

to parliamentary democracy; and in 2012 he contributed to a

larger collection of essays on the topic of the role of the Crown

in Canadian governance. Professor Russell used his

presentation to speak about the broader theme of constitutional monarchy, and its benefits in a parliamentary

system—particularly within the Canadian context.

Professor Russell began by decrying the neglected state of the

Crown as an area of academic study—a state of affairs that he

believes has led to the idea of republicanism being the default

position of many university students today, who can’t get past

the superficial criticism of inherited privilege. While

conceding that constitutional monarchy is a hard sell, he feels

that it is nonetheless important to try and convey its benefits

to a wider audience.

Despite the defects that are inherent in any particular form of

government, Professor Russell firmly believes that

constitutional monarchy is the best solution for Canada’s

particular form of parliamentary democracy. Its chief benefit

is the particular way in which a monarchical government can

separate the positions of head of government and head of

state—which he terms “duality at the top”. Unlike the republic

south of our border, Canada’s monarchical parliamentary

system grants most political power to a partisan prime

minister, while our highest office is reserved for a politically

neutral Queen (and her representatives), who steers clear of

political decisions in all but a few relatively rare situations.

According to Russell, the most important constitutional

function of the Crown is its role in determining who should

form a government that possesses the confidence of the

elected chamber. While it is usually an easy decision to simply

choose a prime minister by appointing the party leader who

has most recently won an election, when there is a hung

parliament, or a divided Cabinet, the decision can become

fraught with controversy. It is particularly in such situations

that Professor Russell believe that we are quite fortunate to

have a non-partisan head of state, able to act as a neutral

political referee and ultimate decision-maker, in order to

protect our democratic traditions.

Russell concedes that the head of state in a parliamentary

system does not have to be a monarch—in fact, in most

parliamentary systems, republican heads of state abound. In

such systems, a president is usually elected indirectly by

parliament (or sometimes directly by the people). A necessary

by-product of this form of government, however, is that the

head of state ends up being someone who has won some sort

of election, and who is almost certainly affiliated with a

political party. While many of these systems work pretty well,

others have gotten into trouble when parliamentary crises

inevitably arise. According to Russell, there is sometimes a

tendency for the democratically elected head of state (who can

lay claim to a certain amount of democratic legitimacy) to

challenge the prime minister—sometimes taking over--

thereby diminishing the duality at the top. Further, a

politically partisan elected head of state can run into

difficulties when exercising the politically neutral functions of

her office.

In a constitutional monarchy, such as Canada, the efficient

role of the Crown in governance has largely been ceded to

elected officials. But the residue remains, primarily in relation

to the life and death of Parliament. Usually these Royal

prerogative powers are exercised on the advise of the head of

government, but in rare exceptions the head of state may act

in her own right when following the advice of her prime

minister (or premier) would be constitutionally wrong, or

dangerous to our democratic traditions. An extreme case,

illustrated by Eugene Forsey, could occur when a prime

minister fails to achieve a desired majority after an election.

Instead of trying to form some sort of parliamentary coalition,

the prime minister might prefer to call a steady stream of

elections, one after the other, in order to achieve the “right”

result. According to Russell, this sort of extreme

electioneering would actually damage democracy, and so it

would be perfectly reasonable to expect our non-partisan

head of state to step in to protect democracy by saying “no” to

the head of government. It is this role in particular that a non-

partisan monarch can often perform better than a partisan

head of state.

While this particular role of the Crown has been likened to a

“constitutional fire extinguisher”, it is actually the “dignified”

role of the Crown that is most visible in Canadian governance,

and—if performed well—can strengthen the “moral sinews of

our democratic society.” Ironically, however, Professor

Russell believes that it is this part of the job that is often

underestimated by academics and intellectuals, who tend to

diminish the important ceremonial role of the monarch and

her representatives.

Like the efficient role of the Crown, it is better to have an

apolitical leader—who can represent the entirety of the state

and its people—perform these ceremonial duties, instead of a

politician who will find it hard to represent anyone other than

the faction of people who support his particular party.

According to Russell, monarchical heads of state, and their

vice-regal representatives, do this part of the job at least as

well, if not better, than republican heads of state. Further, the

Crown has been an invaluable source of unity between the

historic French, English and Aboriginal communities that

make up Canada. And as a Commonwealth Realm, we share

our head of state with 15 other countries around the globe. As

a result, we have a very experienced and international head of

state, unique to world history.

In conclusion, Professor Russell makes some interesting

comments on the origins of constitutional monarchy as a

system of government. Human beings did not invent this

particular form of constitutional monarchy; instead, it is a

governmental institution that has evolved without any

theoretical design, which nonetheless works extremely well.

Russell believes that those people who want to replace it out

of a misplaced ideological sense of correctness, make the

mistake of all children of The Enlightenment, who believe that

their brains are always better than history—a remarkably

foolish assumption. Paraphrasing Hegel, Russell finishes his

talk by declaring that sometimes the cunning of history

produces something that we, here and now, could never

invent. Russell believes that this is the case with the

monarchical solution to the head of state problem in a

parliamentary system.

Father Monet received his doctorate of history from the

University of Toronto in 1964, was ordained a Jesuit priest in

1966, and has taught at a number of schools throughout

Canada. He is director of the Canadian Institute of Jesuit

Studies, and is considered one of Canada’s leading historians.

He has also written extensively on the subject of the Canadian

Crown, and has acted as an advisor to Rideau Hall. Father

Monet is currently a member of the Advisory Committee on

Vice-Regal Appointments.

Father Monet begins his presentation by talking about the

important role of the Crown in relation to French Canada.

French Canada has always been a monarchy; first under the

French Kings, and then under successive British and

Canadian monarchs. Monet believes this uninterrupted reign

of Kings and Queens is unique in Western history, where even

England has suffered from an interregnum period in the 17th

Century. Unfortunately, however, this is a point that is largely

unknown to most Canadians today.

While modern Quebec is largely known for its particular

republican strain of separatism, historically and traditionally

it has strong monarchical roots. Eminent French Canadians,

such as Sir George-Étienne Cartier—one of the fathers of

Confederation—were ardent monarchists, and Monet believes

that under the separatist crust of modern Quebec lays a

largely loyal population. While the Queen was infamously

booed by radical Laval University students in 1964, the Queen

and members of the Royal Family have gone back to Quebec

several times to much better receptions. To this day, the

Governor General has an official residence in Quebec, and the

Lieutenant Governor continues to act as the highest executive

authority in the province—a situation that is unlikely to

change in the foreseeable future. Ironically, according to

Monet, René Lévesque, the separatist premier of the province

leading up to Patriation of the Constitution, was first among

the provincial premiers to agree that modifications to the role

of the Crown should require unanimous consent among the

provinces and the federal government in the new

constitutional structure of Canada.

After discussing the unique status of the monarchy in French

Canada, Father Monet ends his talk with a brief discussion of

the newly-instituted Advisory Committee of Vice-Regal

Appointments. According to Monet, one of the traditional

problems with Canada’s constitutional practice surrounding

the monarchy was that the appointment of the Governor

General or other vice-regal officers has to be done upon the

advice of the Prime Minister—giving past appointments (even

the most upstanding appointees among them) a partisan flair.

This situation has, unfortunately, cast a cloud over vice-regal

appointments.

In order to rectify this problem, Prime Minister Harper

created the non-partisan Committee in 2012 in order to help

make future appointments. The Committee is usually

composed of 5 members—3 permanent members (including

one Anglophone member; one French Canadian member,

represented by Father Monet; and one chairperson, who is

currently also the Canadian Secretary to the Queen) with 5

year terms; and 2 temporary members that are added from

the province or territory from which a vice-regal officer will be

appointed.

The first ad hoc committee (the Governor General

Consultation Committee) met in 2010 to help appoint David

Johnston as our current Governor General. After the

successful work of this initial Committee, the permanent

Advisory Committee on Vice-Regal Appointments was

constituted, and has since appointed several Lieutenant

Governors from among the various provinces, including

Ontario’s most recent Lieutenant Governor, Ms. Dowdeswell.

While conscious of the confidential nature of the Committee,

Father Monet does provide some interesting insight into its

inner workings. First, when it is time to look for a new

appointment, the Prime Minister appoints the two extra

temporary members (if it is a territorial commissioner or

lieutenant governor that is being appointed) and the entire

Committee has a meeting with the Prime Minister (which is

usually by phone). At this meeting the Prime Minister gives

some very vague instructions, and tells the Committee to

come back to him with five names for possible appointees.

There is no order of preference for the 5 candidates—each one

is equally “number one”.

After the Committee has been announced, the various

members of the Committee proceed to speak to various

stakeholders, such as the governments of the relevant

province or territory, and other eminent individuals and

organizations, including the Monarchist League of Canada, in

the search for candidates.

When the first ad hoc Committee was constituted to find the

current Governor General, they had 132 initial candidates,

which were subsequently whittled down over a three day

period to get the 5 nominations that were requested.

According to Father Monet, this process wasn’t easy; between

the first evening and 4 am the next morning, the Committee

was able to get the list down to 20 candidates. However, it

took them a another 2 days to make the remaining cuts.

Finally, after this process is completed, the Prime Minister

meets with the Committee to go over the final candidates, and

asks each member to name their personal preference from

among the list. According to Monet, sometimes each member

of the Committee has his own preference for number 1; while

other times the ultimate preferences are unanimous.

In addition to the current Governor General, who was selected

under the initial ad hoc Committee, the new permanent

Committee has helped to choose several vice-regal officers,

including the Lieutenant Governors of Ontario and Manitoba.

Monet believes that this new process is the best thing that

been has done to strengthen Canada’s monarchical form of

government, and argues that it has effectively addressed the

criticism of partisanship that has attached itself to past

appointees.

While the Prime Minister still ultimately chooses the

appointee, he has limited himself to a list of 5 candidates,

each one of whom has come from a committee that did not

involve the Prime Minister in the nomination process—except

for the brief hour-long meeting at the end, where he asked the

members about their ultimate choices. Father Monet hopes

that this new body lasts long enough that it will become a

constitutional fixture in its own right.

Edited by Kevin Gillespie,

Chair of the Osgoode Constitutional Law Society

RSS Feed

RSS Feed